In his 1999 book, Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age, Michael Hiltzik said that “a certain quality [was] possessed by [the Palo Alto Research Center] in its extraordinary early years”: Magic. And it was the source of multiple seminal technologies including the laser printer, Ethernet and object-oriented programming.

Malcolm Gladwell said, “If you were obsessed with the future in the seventies, you were obsessed with Xerox PARC,” and its unofficial credo was, as Alan Kay, head of the center’s Learning Research Group said, “The best way to predict the future is to invent it!” About his colleagues at PARC, Kay said, “The people here all have track records and are used to dealing lightning with both hands.”

But the best known story about the halcyon days of PARC surrounds the graphical user interface that became ubiquitous on personal computers in the 1980s when it was commercialized by Apple and Microsoft, not Xerox.

In early 1979, Xerox Development Corporation chief Abraham Zarem was exploring the idea of having “a young, hungry company with a modest cost structure” create a marketable product from PARC’s personal computer technology. In April of that year, Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Computer—which was less than four years old at the time—offered XDC an opportunity to purchase Apple stock in exchange for a demo of Xerox technology.

“Apple Computer was scarcely a blip on the radar screen of most PARC engineers,” according to Hiltzik. “They were Ph.D.s who had worked on some of the biggest computing projects the world had ever seen; Apple was a bunch of tinkers.” But Larry Tesler of the PARC Learning Research Group insisted that “if PARC did not change its attitude [about Apple and ‘the growing underground of youthful hackers’]…it was going to look back one of these days and discover it had been passed by.”

Most of the members of the Systems Science Lab at PARC—which was developing most of the innovative personal computer technology—still hoped, however, that “Xerox might eventually get around to bringing out the technology on its own.” And Adele Goldberg “felt adamantly that disclosing PARC’s intellectual property to a team of engineers capable of understanding it and, worse, exploiting it commercially would be a mortal error,” said Hiltzik.

They soon learned, however, that “the engineers could decide how to stage the demo, but Xerox headquarters had decreed that one way or another, it was going to happen,” Hiltzik said.

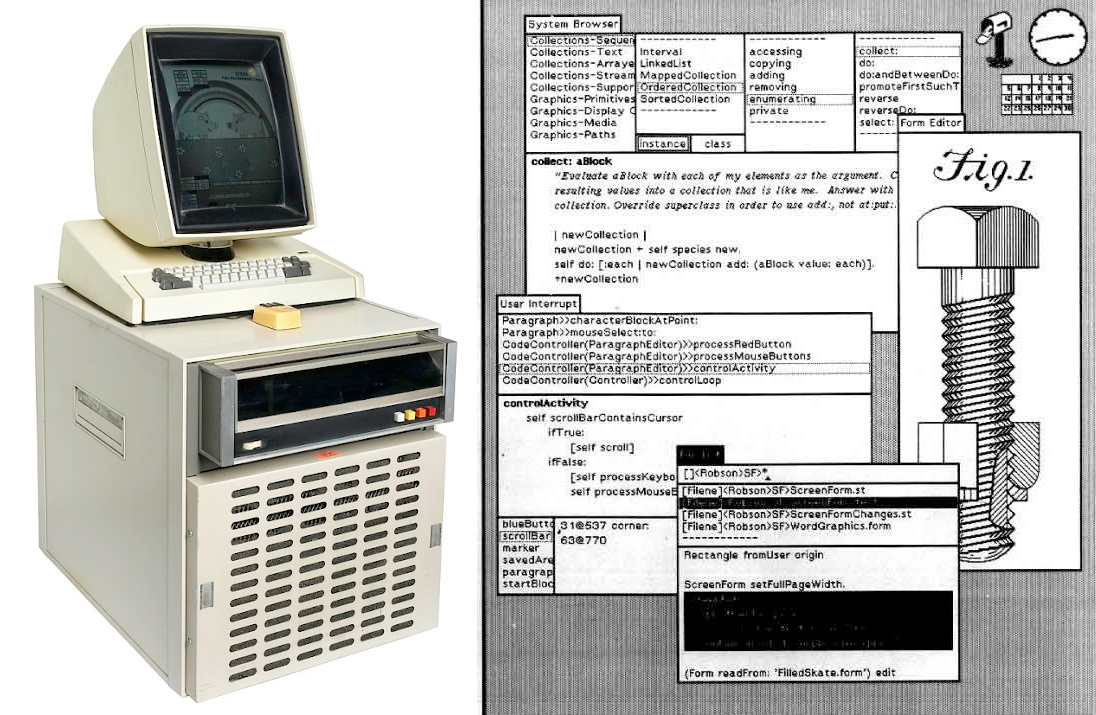

At PARC in December, 1979, members of Kay’s Learning Research Group—including Goldberg, Tesler, Dan Ingalls and Diana Merry—gave a thoroughly sanitized demo on an Alto computer to a group including Jobs, Apple president Mike Scott and programmer Bill Atkinson. “It was very much a here’s-a-word-processor-there’s-a-drawing-tool demo of what was working at the time,” said Goldberg. “No harm done, no problem. What they saw, everyone had seen. The conversation they had with us, everyone had. There was no reason not to do it, it was fine.”

Significantly, they had not shown Apple the Smalltalk programming language, which was the foundation of the user interface and functionality they had seen. Jobs, who had been “skeptical of what PARC might have to offer,” seemed satisfied when he left, but he quickly learned that much had been left out of the demo.

A team of ten or so Apple people appeared at PARC again two days later, determined to learn more. Scott and Xerox’s Harold Hall danced around the issues in “executive-speak” for several minutes while Jobs waited impatiently, according to Hiltzik. Then Jobs jumped from his chair, saying, “There’s no point trying to keep all these secrets.” He said to Scott, “These guys think we’re going to make the Xerox computer, but we all know we want them to help us with the Lisa!” Xerox knew nothing about any Apple computer called Lisa.

As the rest of the Apple team sat dumbstruck, an Apple engineer broke the awkward silence, explaining, “Lisa is an office computer we’ve designed with a bitmapped screen and a simple user interface. We think some of your technology would be useful in helping us make the machine easier to use.”

Tesler knew that the Smalltalk interface, parts of which Apple had not seen, would indeed make Apple’s computer easier to use, and he was eager to demonstrate it fully: “If Xerox was not going to market a personal computer, why should all the Learning Research Group’s work simply go to waste?,” Hiltzik believed Tesler was thinking. But Goldberg, co-developer of Smalltalk with Alan Kay, insisted it would take a direct order from Xerox corporate to overcome her objections. With amazing speed, the order came from Bill Souders, executive vice president and head of Xerox’s business planning group in Stamford, Connecticut, who ordered the demo team to give Apple the “confidential briefing.”

As they demonstrated the full power of Smalltalk via programs with “capabilities that had never been seen in a research prototype anywhere, much less in a commercial system,” the Apple engineers watched with rapt attention. Atkinson, particularly, “was asking extremely intelligent questions that he couldn’t have thought of just by watching the screen,” according to Tesler. “It turned out later that they had read every paper we’d published, and the demo was just reminding them of things they wanted to ask us…They asked all the right questions and understood all the answers. It was clear to me that they understood what we had a lot better than Xerox did.”

According to Tesler, “Jobs was waving his arms around, saying, ‘Why hasn’t this company brought this to market?’” Jobs claimed afterward that after seeing the demo, he knew that “every computer would work this way some day,” but the developers of the Lisa had already designed their own GUI. Theirs was “far more static than the Alto’s” and placed much less reliance on the mouse, but Atkinson, who’d been stuck for months on several programming problems, had his confidence boosted by the demo and was finally able to solve the problems in his own way. “That whirlwind tour left an impression on me,” Atkinson said. “Knowing it could be done empowered me to invent a way it could be done,” and in fact, several of Atkinson’s solutions proved to be much more effective than Xerox’s. According to Hiltzer, Atkinson “resented the importance others have attached to his visit to PARC: ‘In hindsight I would rather we’d never have gone,’ Atkinson said. ‘Those one and a half hours tainted everything we did, and so much of what we did was original research.’”

Apple’s work was not “serial reproduction…[but] the evolution of a concept,” Malcolm Gladwell said. “Jobs’s software team took the graphical interface a giant step further…It emphasized ‘direct manipulation.’ If you wanted to make a window bigger, you just pulled on its corner and made it bigger; if you wanted to move a window across the screen, you just grabbed it and moved it. The Apple designers also invented the menu bar, the pull-down menu, and the trash can—all features that radically simplified the original Xerox PARC idea.”

“The difference between direct and indirect manipulation,” Gladwell insisted, “is the difference between something intended for experts, which is what Xerox PARC had in mind, and something that’s appropriate for a mass audience, which is what Apple had in mind. PARC was building a personal computer. Apple wanted to build a popular computer.”

Indeed, Apple was influenced by their exposure to Xerox’s technology but, according to Hiltzer, the visits may have affected the PARC scientists even more. Jobs’ “fanatic enthusiasm for their work hit them like a lightning bolt. It was a powerful sign that the outside world would welcome all they had achieved within their moated palace while toiling for an indifferent Xerox.”

In 1980, Apple asked to license Smalltalk for use in the Lisa but was turned down. Instead, they hired Larry Tesler, and he became the head of the Lisa interface team, helped design the Macintosh and became Apple’s chief scientist.

According to Malcolm Gladwell, the engineers at PARC “weren’t the source of disciplined strategic insights. They were wild geysers of creative energy.” The common characterization of Xerox as unable to bring new technologies to market, said Hiltzer, “presupposes that a corporation should invariably be able to recoup its investment in all its basic research,” and overlooks Xerox’s generous funding of PARC through decades of tumultuous change in the computer industry. And he insisted, “Apple was able to market the PC not in spite of its small size, but because of it.”

In Making the Macintosh, Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, Stanford University librarian and historian, said, “Turning expensive, hard-to-use, precision instruments into cheap, mass-producible, and reliable commercial products requires its own ingenuity and creativity. This marketplace intelligence is different from, but not inferior to, the intelligence of the laboratory; it just gets far less attention by journalists and historians.”